/Xv6 Rust 0x03/ - Memory Virtualization

We have learnt how to setup risc-v in rust, and also initialized risc-v to be able to print format strings, in this chapter we are taking the first look of the OS kernel, and will try to figure out the memory management in xv6.

1. Overview of physical memory

Before we get any further, let's recall the memory mapping in the QEMU that we mentioned in previous chapters:

1 | qemu-system-riscv64 -monitor stdio |

As we can see, the range of RAM is from 0x80000000 to

0x87ffffff, which exactly to be 128MiB, and that is because

we set it to be 128MiB in the runner command.

And let's take a look at the kernel.ld

in the xv6-rust repo:

1 | OUTPUT_ARCH( "riscv" ) |

It's a little bit more complicated than the one we wrote in the previous chapters, but still quite clear.

Let's ignore the complicated part in the middle of the file, only

focus on the PROVIDE(***) lines:

1 | /* define a symbol named "etext", and set its value |

We can imagine, before etext, the program lies there and

cannot be changed, between etext and end, any

read-only data, writable data and bss data are put there, after

end, the rest of the RAM space is available for stack or

heap. Here are the real symbol addresses:

1 | readelf -s kernel | grep -E "etext|stack0|end" |

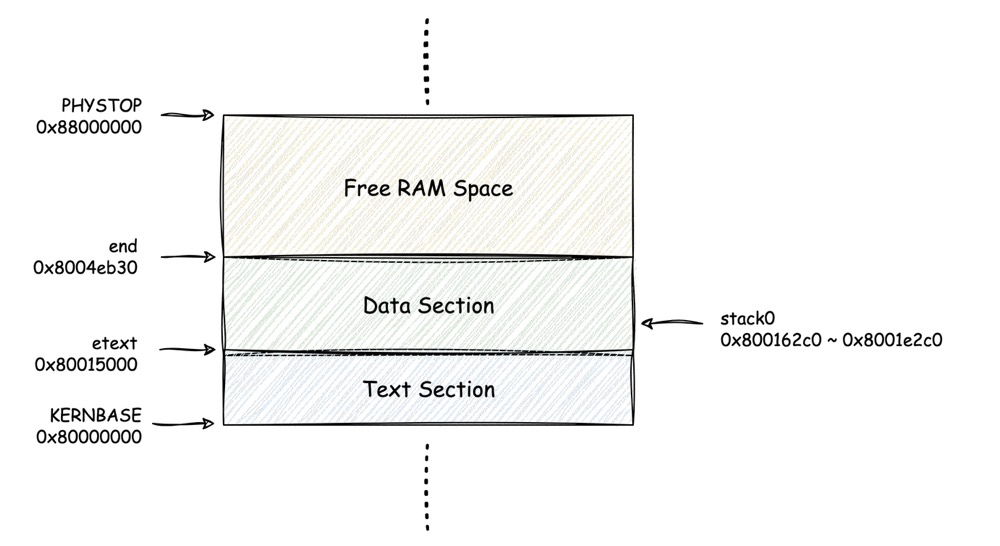

Hence, we could get the simple RAM map as follows:

And the interesting thing is, if you take one more step to check the

section addresses by readelf, you'll find the

stack0 was actually located in the rodata

section, because we define it as a static field in the start.rs,

but we use the stack0 as the kernel stack, which is

writable.

The reason why we can write a read-only field without an exception,

is at the beginning of start() we access it in the machine

mode, and afterward we set the Physical Memory Protection to RWX across

the range of 0~0x3ffffffffffff, according to the last

chapter, so that in the supervisor mode, the stack0 can

also be written.

2. Memory allocator

So far we have known the physical RAM space, next let's see how to manage the RAM space so that it can easily be allocated and returned back.

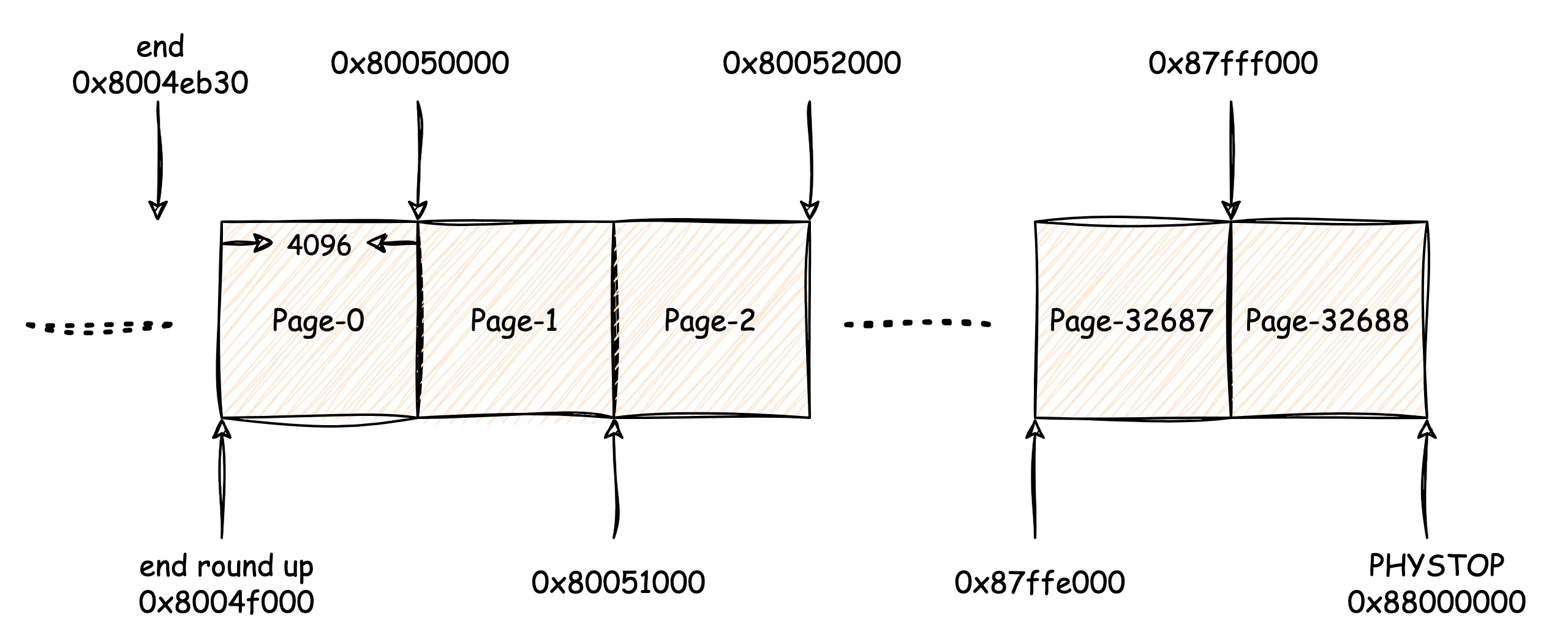

In xv6, the smallest unit of memory management is "page", which is

4096B by default, and we can adjust the page size by setting the PGSIZE.

Basically RAM management divide the RAM into numerous and consistent

pages, like this:

So now we have divided the RAM into 32689 pages, how to track them? How to allocate pages to some code that needs the exact amount of memory? And how to recycle them in the end?

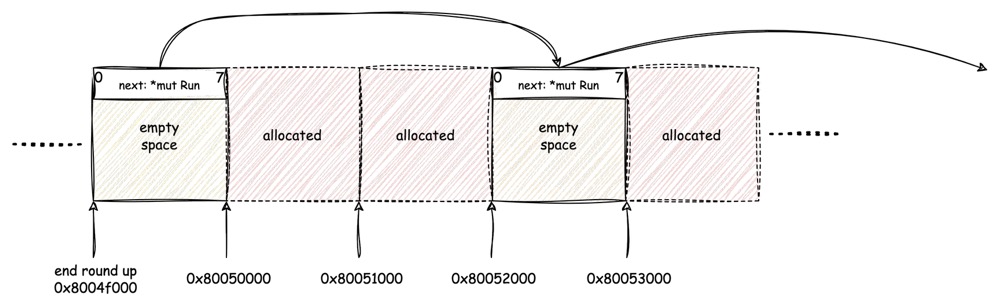

Xv6 using the implicit list to track them, and each list item called

a Run:

1 | // kalloc.rs |

It's very simple to understand, the list actually only track the free

pages, so the next pointer can directly put into the page

space itself, avoid introducing any extra memory space to save the

pointer. Once a page has been allocated, the whole 4096B can be used to

store data, when it returns back, we can find the correct position of

that page by calculating its address.

Based on the above image, we can better realize how xv6 manages its

RAM. During the kernel starting, the available RAM space will be

initialized by divided into pages, and fill with junk data, such logic

starts from kinit():

1 | // kalloc.rs |

When the initialize completed, then any kernel code could call kalloc()

to get one page of available memory:

1 | // kalloc.rs |

Apparently xv6 implemented a very simple memory allocate mechanism, which totally avoids introducing any lazy allocation here, hence, page fault is also treated as ordinary exceptions and kernel would crash if page fault happens.

Please note that, till then all of the addresses and pages we have talked about are physical memory. Actually before a page has been used, its address must be converted to the virtual address. Next we'll go to the virtual memory part.

3. Virtual Memory

Virtual memory mechanism is the key to achieve the memory virtualization, modern processes usually support virtual memory in hardware level, which includes address translation, permission control and related interrupts.

In risc-v architecture, virtual memory management is based on page, variety of page table structure modes are supported in risc-v, like Sv32, Sv39 and Sv48, even Sv52, the number behind the "Sv" indicates the address width, for example, "Sv39" is the short for "Supervisor Virtual addressing with 39-bit virtual addresses", which means under the Sv39 mode, the virtual address space that a process can accessing is \(2^{39}\) bytes that around 512GiB.

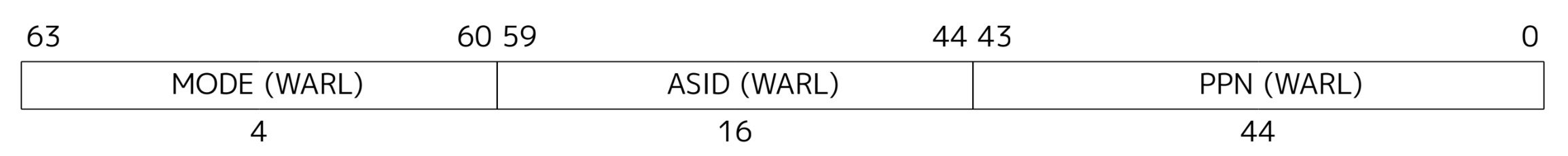

Let's recap the satp CSR mentioned in the last chapter,

and go one step deeper(more details please see The

RISC-V Instruction Set Manual: Volume II: 10.1.11.):

The above image is the definition of satp, it contains

three parts, the first part defines the mode, like the following

image:

Xv6 uses risc-v64 and Sv39, so the highest 4bit would be

0x8.

The second part "ASID" basically provides better performance by allowing OS to hint TLB through it, however, xv6 doesn't use this feature.

The third part "PPN" is called physical page number, the

stap.PPN should be set to the PPN of the root page table,

so that the processor can find page table through it.

Talking about the page table, what exactly is the page table structure defined in Sv39? Let's have a look, in the meantime, there are many more details in The RISC-V Instruction Set Manual: Volume II: 10.3 ~ 10.6., please check it if you are interested.

In fact, not only risc-v, almost all page tables share the concept of multi-level page table entries. We can have an example to make it clearer for understanding:

Say we have a variable a located in a process's stack,

whose virtual address is 0x3f_fff7_e000(you'll know why we

choose such a bug number afterward in the following sections). And we

assume its physical address is 0x80050000, so if we need a

page table right now to hold such mapping relationship, the simplest way

is having an array to act as a table, like this:

If we don't yet care how we got such a huge array, which size is exactly the same as the 39-bit space, the index of the array represents virtual address, while the value represents physical address. This at least makes our "theoretically" page table available.

But there's no doubt that this won't work. Considering 99.99% of the above page table are not been used, but the space still need to be occupied since array is consistent. Can we use more space efficient way like linked list? Not really, because address translation is a very high frequency operation which requires very low latency.

Then multi-level page table turns out to be the final solution:

With the multi-level approach, only a few of page tables will be

created, like the above image, if we want to store the mapping

0x3f_fff7_e000 -> 0x80050000, we only need for

512-entries page table, assume an entry store a 64-bit number(the first

three store the next page table address, the last one store the physical

address), then they only take \(512 * 8 * 4 =

16\ KiB\) space in total. Calculate each level's table index is

simply left shift the virtual address for a few bits, please check the

detail in the function walk().

More importantly, the virtual memory structure manages memory by page, one page in Sv39 is 4096-bit, which is \(2^{12}\), therefore, actually we don't need the low 12 bits at all, since the last 12 bits in each page is 12 bits 0. risc-v make use of this 12-bit to record permissions. The following image shows format of virtual address, physical address and PTE(page table entry) in Sv39:

The PTE flags R, W, X indicate

the read, write and execute permission of the PTE, U indicates user

mode, V use to identify if the PTE is valid.

4. Initialize kernel virtual memory

We already mentioned before that although kalloc()

allocate memory directly form physical memory, no matter kernel code or

user code, they all running on virtual memory. The only difference here

is, kernel virtual address space is on purposely as same as physical

address, while user virtual address starts from 0x0.

Let's have a first look at kvminit(),

which is the initialization of virtual memory:

1 | // vm.rs |

The above code is very important since it maps all physical addresses to virtual space, which includes uart, virtio, PLIC(we'll cover these two in later chapters), and it also maps kernel text section with RX permission, kernel data section and RAM with RW permission.

Besides, it maps "TRAMPOLINE", which is a special address block that takes over the logic of user jump to kernel in every process, we'll cover this part in a later chapter as well.

The interesting things here are, all the above virtual addresses are exactly as same as their physical address. The reason why design like that, is because there is only one kernel, and only one uart device or PLIC. Virtual memory mainly provides virtualization to processes in user space, but in order to share a same address space across all kernel, devices, and user, it's necessary to map them to virtual space too.

The actual implementation of mappages()

involves some detail about building the page table, we'll omit this part

since we've already figured out how page table works in the previous

content. Please check the code directly.

After kvminit(), there is one more step to make it

effective, which is contained in the kvminithart():

1 | // vm.rs |

Essentially it just set the KERNEL_PAGETABLE, which is

built before in the kvminit(), into satp,

after that, any memory access in any instruction will lead to page

translation through the KERNEL_PAGETABLE in the first

place.

I suppose you may have noticed that there are still many functions

inside the vm.rs left, which we haven't talked about, most

of them are related to process or user space memory management, let's

cover them together with CPU virtualization in the next chapter!