/Xv6 Rust 0x05/ - Persistence

With all of the content in the previous chapters, we have known how to initialize and run a process, but before the kernel runs the first line of a process's code, a question still remained, how does my user program store in the disk and how is it loaded?

In this chapter, we are going to discover the disk management and file system in the xv6, we'll see the persistence stack from the top to the bottom, let's get started!

1. Overview of Persistence

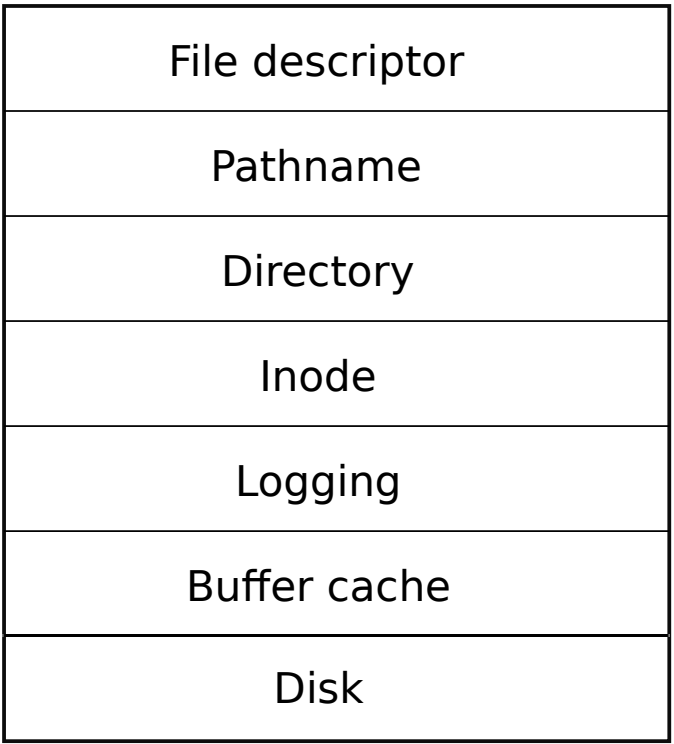

The xv6 designs a very clear persistence system, which is designed by layers. The xv6-book demonstrates a diagram(in chapter 8) to show such layers as follows:

Actually, the first three layers are all related to the concept of "File". The xv6 inherits the unix philosophy of "everything is a file", which is a high level abstraction that regards all devices, pipes, directories, and disk files as "Files", to simplify access and management. Each file has a unique file descriptor that let it to be identified conveniently, file descriptor is also the name of the first layer.

Let's have a first look at the structure File:

1 | // file.rs |

The FDType

stands for "file descriptor type", apparently there are three different

types of file descriptors except for the "NONE". The "PIPE" indicates a

communication channel between two processes, and a pipe is completely

lives in memory; the "DEVICE" indicates some kind of device like the

UART console, which can be operated by reading and writing data; the

"INODE" indicates a type of object that holds some data blocks in the

disk.

Looking into the File

structure, it holds some fields that represent different types of files.

For example, both the fields pipe and ip are

type of "Option", which means they may exist in a file or not. Say a

pipe file, it would only need the pipe field, all other

fields corresponding to inode or device can be empty.

The other two layers, "pathname" and "directory" represent the way to

access and manage file. Path name provides a hierarchical way to locate

a specific file, like /home/lenshood/video.mkv, while the

directory is dedicated for a special type of file that holds all

subdirectory files as its data, a directory is like

/home/lenshood/.

While File

act as a high-level abstraction object that exists in most of syscalls

related to file systems. Here are some typical syscalls:

1 | // user/ulib/stubs.rs |

Apparently, some of the syscalls using fd as their

argument to locate a File,

but open, exec and mknod using

path instead of fd, since these syscalls are

only applicable to files that backed by inodes, and each inode has a

path.

As an example, the following code piece is taken from the

implementation of the syscall read:

1 | // file/file.rs |

The structure is quite clear. Based on the three different types of files, it reads data from a pipe, an inode or a device, respectively.

2. File Organization

Because the file system on disk is very important and complicated, now we are focusing on the file and dir that are organized by the inode system. And we'll leave the device and pipe part at the end.

As we mentioned before, inode is an object that holds the data of file or directory, and it's placed on the disk. So basically all of the files and directories are stored as form of inode on the disk.

The problem is, we see the disk as a very big array (like memory but commonly slower and bigger), so how to effectively put the file and directory on this array, organized as the path name hierarchy, and at the same time, how to easily perform create, update and delete?

Generally, most of the file systems are implemented by splitting the entire disk as multiple sections, some section records the metadata, some sections store file, and some sections just stay empty for future use. The file system in the xv6 is also designed like that, but much simpler.

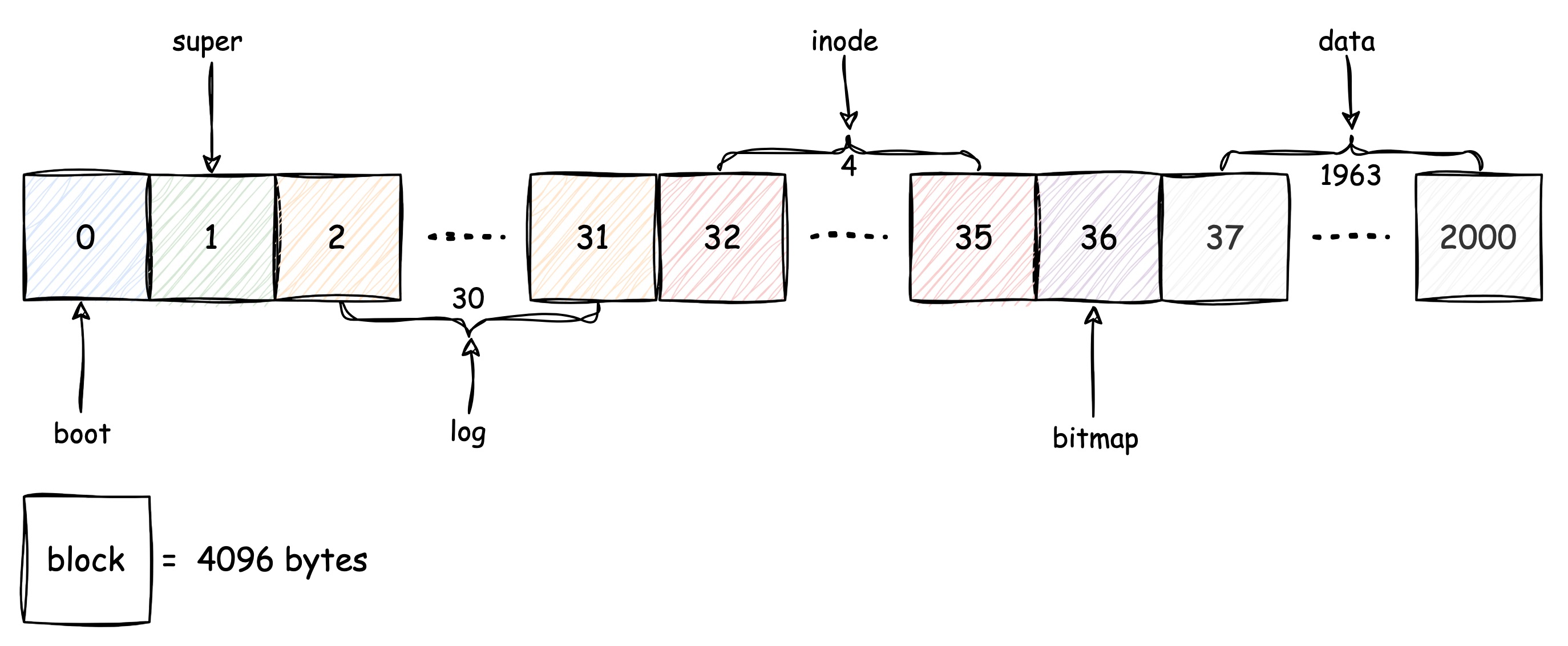

The following diagram describes the disk section structure for the xv6:

We can see from the above diagram that the entire disk has been divided as numerous same sized blocks, each block has size of 4096 bytes. That gives the file system the minimum control unit, which is one block. And each block has its own number, starting from 0.

Based on block, a disk image can be divided into these six sections:

- Boot Section (block 0): size of 1 block, no particular purpose, it stays empty since the xv6 defines meaningful block starts from No.1

- Super Section (block 1): size of 1 block, it contains the metadata of the file system, including magic number, the size of the entire image and the size of other sections, we'll check it soon after.

- Log Section (block 2~31): size of 30 blocks, it mainly records the disk operation logs for recovery purpose, we'll check it soon after.

- INode Section (block 32~35): size of 4 blocks, the inode was designed to store its metadata and real data separately, these 4 blocks only store the metadata part of all inodes.

- Bitmap Section (block 36): size of 1 block, as we know the bitmap is a very efficiency data structure to indicate huge statuses by a few spaces, here is the same way, bitmap section using 1 block to indicate the occupied blocks and empty blocks in the entire disk.

- Data Section (block 37~2000): size of 1963 blocks, the real files data store in this section, which you can notice takes the most blocks of the disk. The end block 2000 was defined by a constant, and can be changed, but more data blocks also means more inodes, so extending the size of data section may need to extend inode section as well.

Firstly, let's take a look at the SuperBlock:

1 | // fs/fs.rs |

As a place to hold the metadata of the file system, SuperBlock

holds the data that is very essential, if we see the initialize of SuperBlock

in the mkfs,

there are FSMAGIC,

FSSIZE,

NBLOCKS,

NINODES,

NLOG

and other constants are assigned, these constants define the block size

of several sections.

2.1 INode

We have been talking about the inode even though we don't know what exactly the inode is, because the inode is a really important concept in the file system and we can barely avoid it. Now let's deep dive into the "inode layer" to find out why it's so important.

First, we should have a look at the INode

structure:

1 | // file/mod.rs |

Surprise! There are two inode structures actually, and that makes total sense. Because the inode would not only exist in memory, but also persistent on disk.

Comparing the two forms of inodes, the memory version of INode

has a few more fields than the disk version, such as lock

and ref_cnt for concurrently accessing, and

inum for identification.

Besides, the disk version of DINode

is very compact in its structure, that's good for store in block and

easy to calculate the location in the disk. Let's calculate the real

size of one DINode

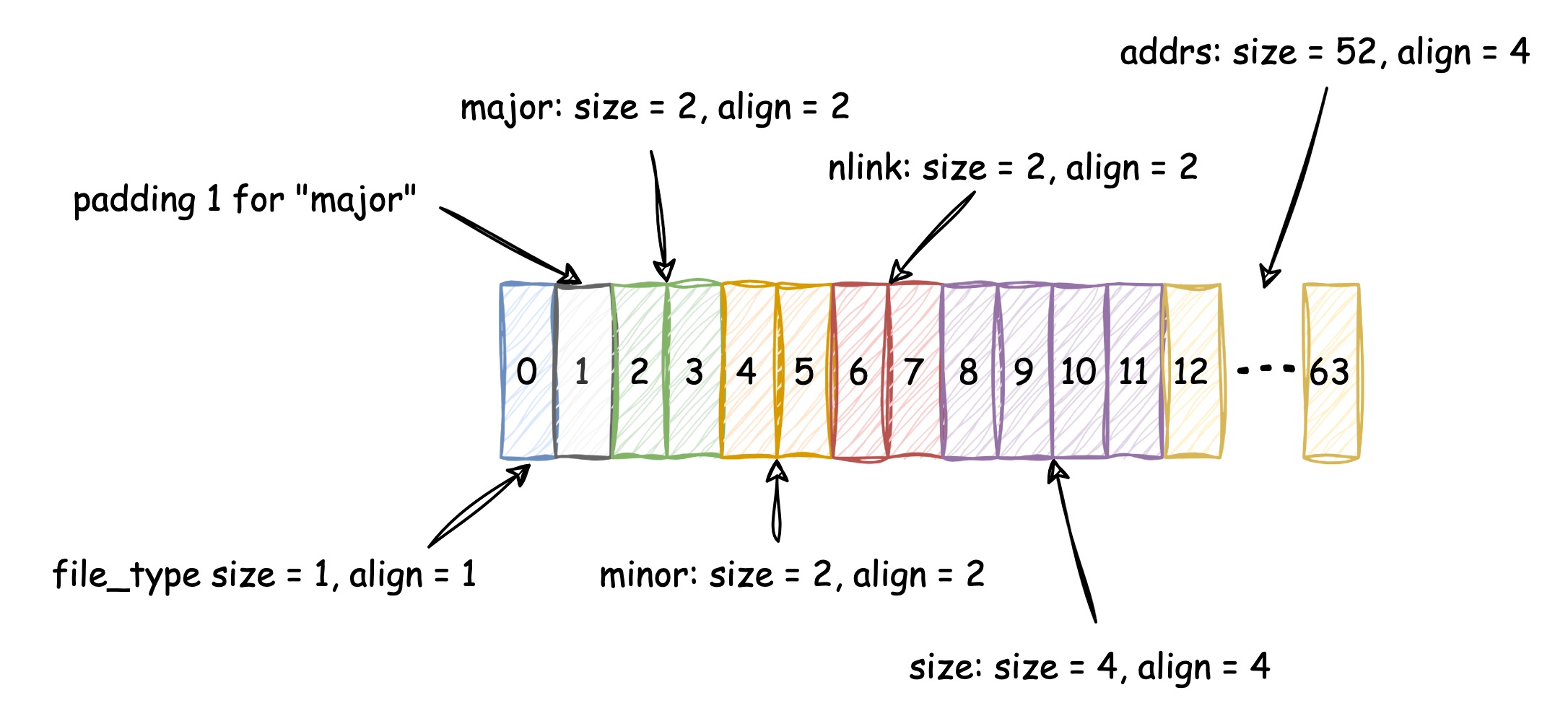

by its fields:

- file_type: 1 byte. (Rust allocate enumeration's size dynamically based

on the number of elements defined in the

enum, since theFileTypehas only 4 elements, 1 byte of space is enough for them.) - major:

i16== 2 bytes - minor:

i16== 2 bytes - nlink:

i16== 2 bytes - size:

u32== 4 bytes - addrs:

NDIRECT== 12, so the size of addrs is 4 * (12 + 1) = 52 bytes

Therefore, if we simply add them together, then one DINode

takes 63 bytes of space on disk. However, like other programs languages,

values in rust also have alignment beside size. In the

rust representation, the fields in a struct can be reordered, and

aligned, so we cannot confidently say the size of DINode

is 63 bytes.

Additionally, you may notice that the #[repr(C)]

has been put on the DINode,

which makes sure the compiler keeps the memory layout of the type

exactly the same as the type defined in C language. According to the

size and alignment principle of #[repr(C)], we can have the

following diagram to help us calculate the real size:

And based on the above diagram, the real size of DINode

is 64 bytes.

So why is it so important to calculate the real size of DINode?

Because next we'll talk about how the inodes stay in the disk.

We have known that there is a section in the disk which takes 4

blocks to hold the inode, but only inode metadata, the data of inode

stores in another location. Refer to the DINode,

except for the last field addrs, all other fields can be

seen as metadata of inode, the last field addrs stores the

reference of the data blocks, which is block number.

Hence, I guess you already figured out how the metadata and real data

of inode store in the disk: the inode section stores DINode,

while the data section stores the data blocks, which block numbers are

stored in the DINode

as references.

So far, I suppose we can do a simple math to prove why we should 4 blocks for the inode section:

First, NINODES

in the super block defines the max number of inodes the file system can

have, the value by default is 200. Then we already know one DINode

takes 64 bytes of space, so 200 inodes will need 12800 bytes to be

saved. A block can store 4096 bytes data, since

12800 / 4096 = 3.125, which means the inode section will

need at least 4 blocks.

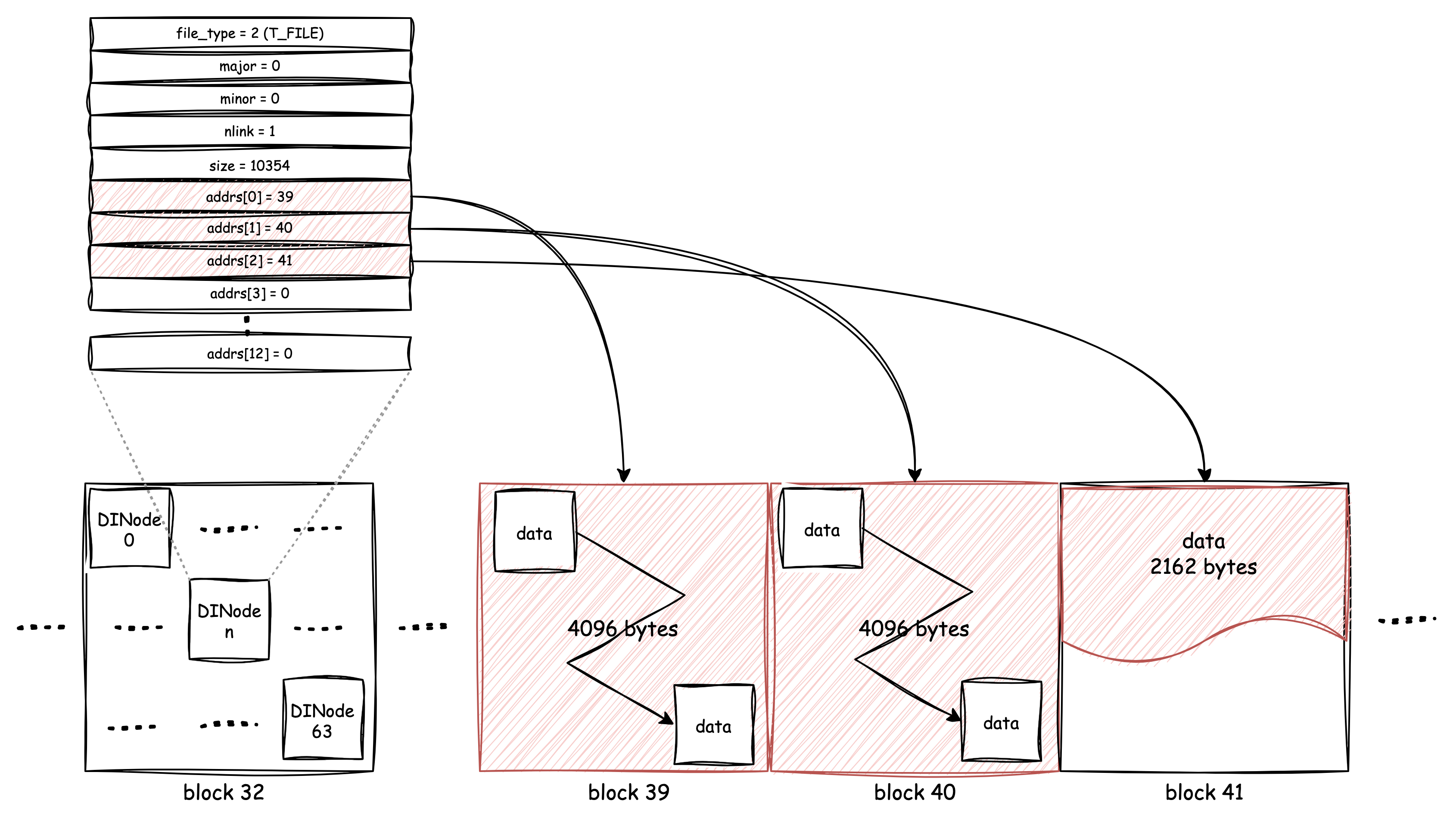

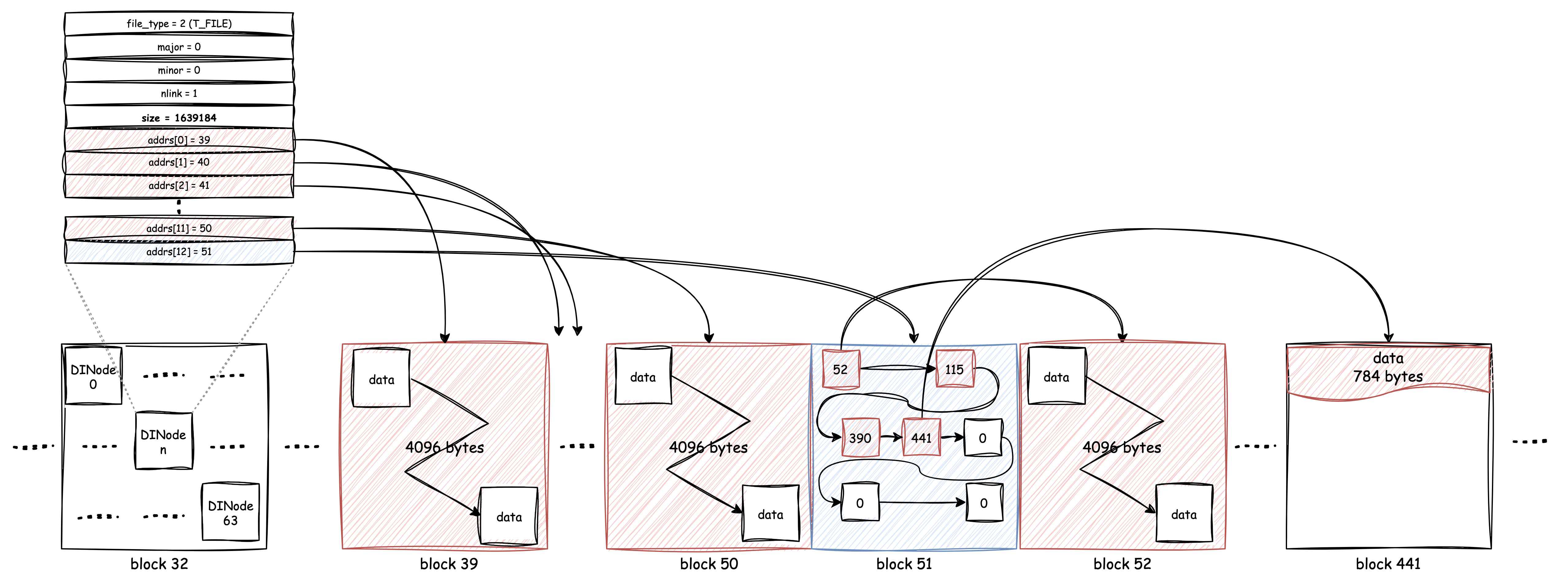

The following diagram shows an inode and the placement of its metadata and real data:

In the above example, the DINode

has 10354 bytes of data, and that will need 3 blocks to store. But what

if the size of data is too large to be stored within 13 blocks?

Actually, in the addrs[], only the first 12 blocks are used

for store data, the number 13th block is specifically designed for more

data. If the first 12 blocks are full, but there is still some data that

needs to be stored, at that time, block 13 will become a big array

dedicated to store block references.

In the addrs[], the first 12 blocks are called direct

data blocks, which can be referenced from addrs[] directly,

and the data blocks that exceeds 12, are called indirect data blocks,

all of the block number of indirect blocks are stored in the 13th

block.

Let's see if the data size exceeds 12 blocks:

So this time we assume the size is 1639184 bytes, which will need 401

blocks, with the indirect blocks, they can be easily stored. Since the

size of a block is 4096 bytes, and a u32 block number takes

4 bytes to store, in theory, the maximum size of a single file in xv6

would be 4MiB.

2.2 Pathname & Directory

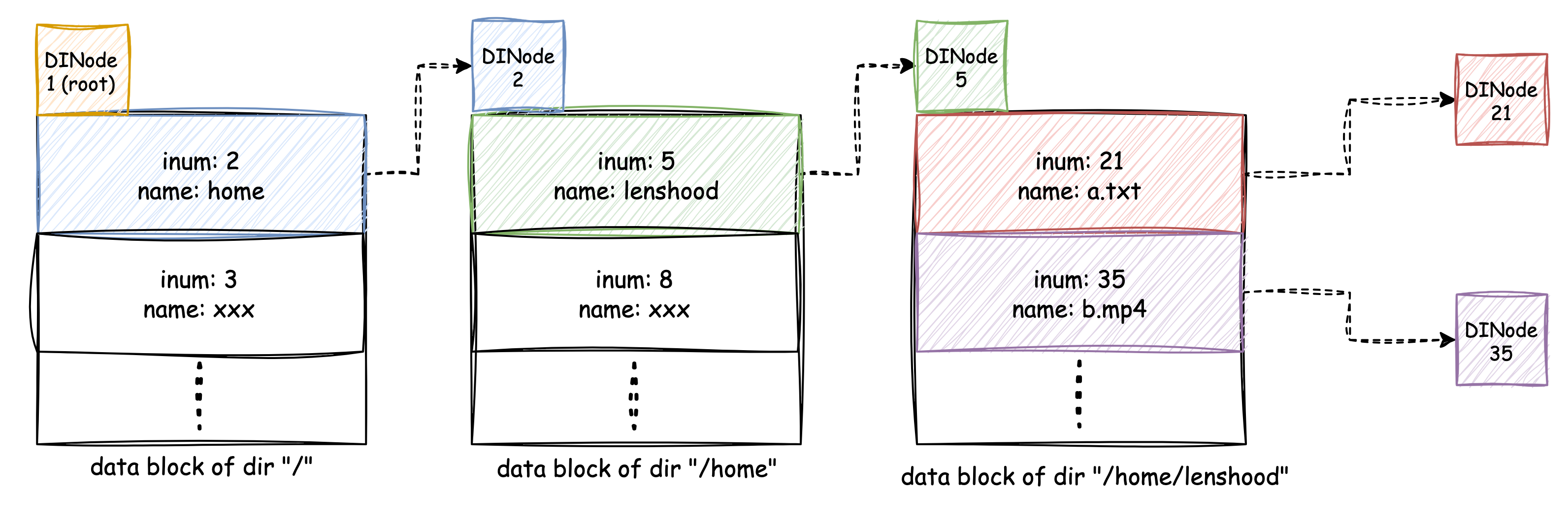

With the knowledge of inode, now we can have a look at the "directory". In the file system, a directory is also considered as an inode file, no matter the path of itself, or the paths of its sub directories or sub files, are all treated as plain data.

This is the definition of directory entry:

1 | // fs/mod.rs |

Directory is a file containing a sequence of Dirent

structures. And the interesting thing is that a directory file only

contains the paths of its subdirectories and subfiles, its own path, on

the other hand, is contained in its parent's file.

The following image shows an example of

/home/lenshood:

So far we've seen the INode related structures and designs, which

help us understand how INode level works. Thus, we are going to omit the

INode operations, please check them at the fs.rs to see

more details.

2.3 Log

Under the INode level, there is another important abstraction level called "log". Generally speaking, log level isn't responsible for any complex logic, it only cares about how to reduce the risk of disk write interruption if a crash occurs. Basically, the log level is building on the concept of "redo log". For the system that runs in the real world, we must assume crash will definitely happen someday.

So if there is no mechanism to take care of the crash, then it has possibility that some disk write operations are ongoing while a power off crash occurs, lead to some blocks were written but some other blocks were not. Since we don't have any idea about what kind of data was in the block, the crash may cause a block has already been assigned to an INode (metadata is saved), but the assigned flag failed to save in the block. That's a serious problem because the kernel may reassign the block that it believes is a free block, to another INode.

But don't give me wrong, the key thing that the log level should keep, is not "recovery", but "consistency", because data inconsistent is way more serious than data loss. The problem we just described above can turn the system into a total disaster because no one can simply tell which INode the block should belong to, comparing that, a data loss is more controllable as we should only revise the data in a few minutes before crash. There's another reason that we care more about consistency than recovery: keep no data loss sometimes too costly, the performance should also be considered, otherwise nobody would use the system.

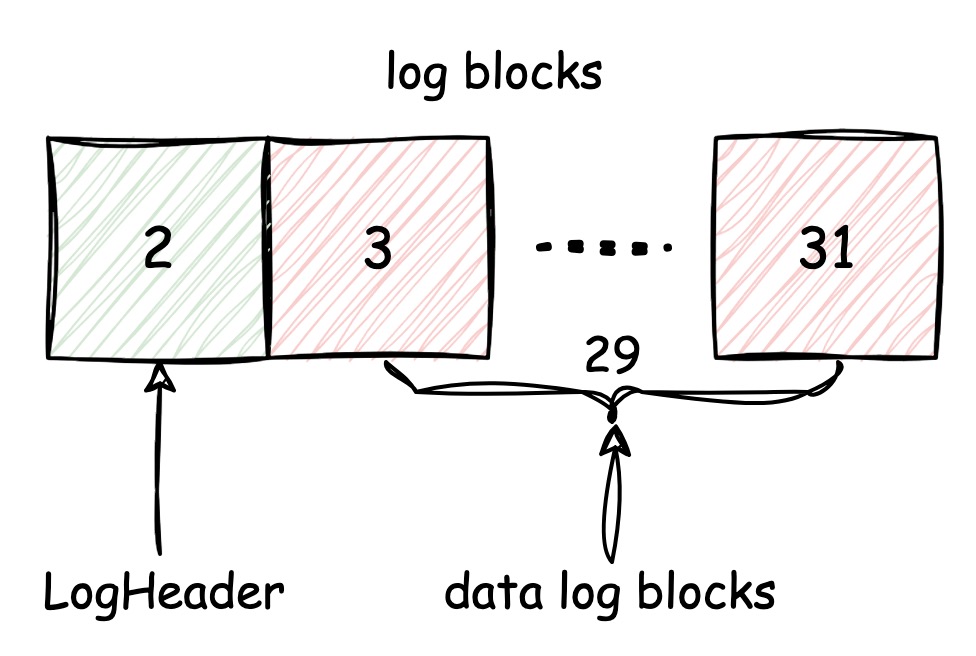

To learn how log level works, let's look deeper into the log blocks:

We know there are 30 blocks reserved for log, but only the last 29

blocks are used for save data, the first log block is for the LogHeader:

1 | struct LogHeader { |

LogHeader

is very simple, n represents how many blocks are saved in

log currently, and block records the block number where the

log blocks map to the real blocks.

When an fs syscall is executing to write data into disk, it first

calls begin_op()

indicating a disk write transaction has begun. Next, rather than

directly call block write method, it just calls log_write()

and return, actually the writing operation is not executed synchronously

at that time, the log-related code will make sure the data is eventually

written, but by an asynchronously way. After all things are done, the

syscall will call end_op()

to finish the transaction.

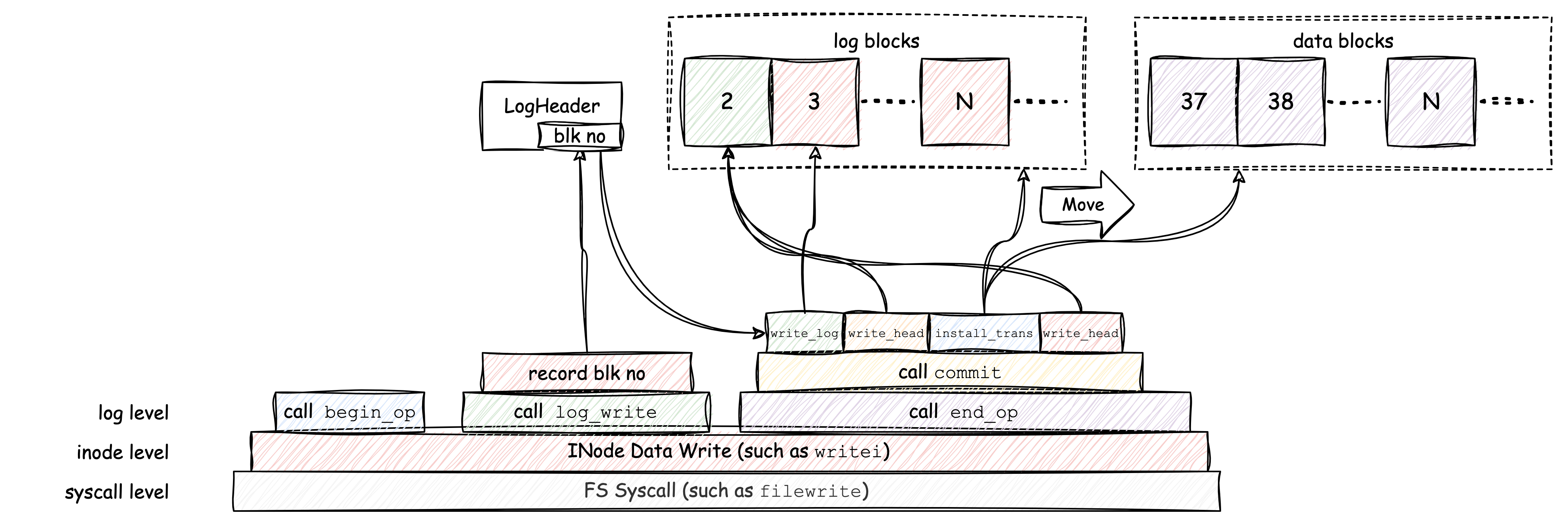

The following diagram may describe the data write process clearer:

The log_write()

will only record the block number of the block that has updates. BTW, if

a block was updated, before it goes to disk, there is a block cache to

hold the block data temporary in the memory, we'll talk about the block

cache later.

When the end_op()

is called, if there is no other log write operation on going, the data

will be written. First the data will be written into log blocks, then

writes the log header. After that, commit has been successfully

executed, and if crash occurs at this point, all of the data saved in

log can be recovered, but before that, all data will be lost, even if

the log blocks are already written. This is how the log mechanism keeps

the data writing atomically and consistency. (Here also implies that,

the operation of writing log header must be atomically, we can imagine

if some parts of log header are successfully written, but some parts are

not, the inconsistency remains.)

After log header is saved, the log blocks will be moved to real blocks, this process is exactly the same as the recovery process. When system started, it will check the log header first, if any log blocks are found, the recovery process will be executed to recover data into real blocks.

3. Block Operation

Beneath the log, we finally arrive at the practical block operations

level. Like we mentioned in the log section, the log level is only for

recovery, so that it only cares about writing rather than reading.

Actually if we check the INode operation code, we will notice many

low-level block operations such as bread(),

brelse().

The INode operations read or write its data through these low-level

block operations.

An INode represents an individual file (here we only talk disk file specifically), but a disk file needs more than one block to store its data, because in block level, block is the smallest control unit and a block can only hold 4096 bytes of data. Here we should always make our mind clear that we cannot simply operate the data structure placed in the disk, like INode, or block, as long as we want to retrieve from or make changes to those data structures, load them into memory is the very first thing we should do.

Just like the DINode,

block also has its memory form, which is called Buf:

1 | // fs/mode.rs |

Buf

holds many fields to record its latest states as a memory block, such as

blockno and refcnt. But we cannot actually

load all of the blocks into memory, which also makes no sense, because

essentially memory is like a cache to the disk, just like the CPU cache

caches data from memory (see Memory

Hierarchy).

So there should be some kind of structure to hold the limit numbers

of memory blocks, and deal with the situation like a disk block wants to

be loaded into memory, while there is no empty memory block

(Buf) left.

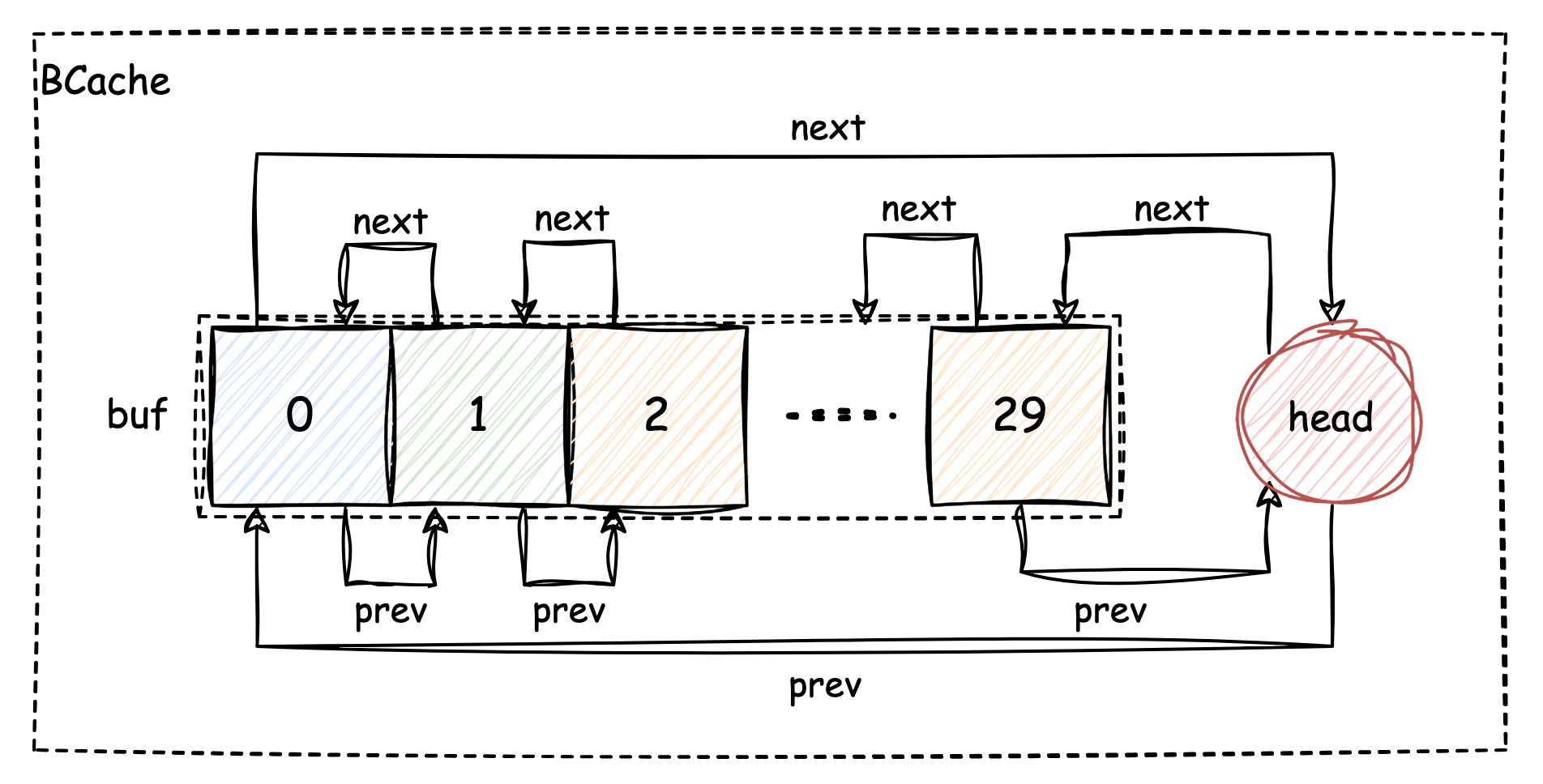

The xv6 introduced a structure called BCache,

which is a combined structure of array list and linked list, to act as

the block cache in memory:

1 | // bio.rs |

It's very simple because it only holds Buf

as an array list, the Buf

itself records prev and next to become a list

with each other, that list makes use of LRU replacement algorithm to

decide which one should be replaced if the cache is full.

The following diagram shows the initial structure of BCache:

The buf array contains 30 Buf

as the memory cache, each element is a memory block frame that can hold

actual data. They are also linked together, with a unique

head.

Refer to the code of bget(),

we may find out how the BCache

works:

1 | // bio.rs |

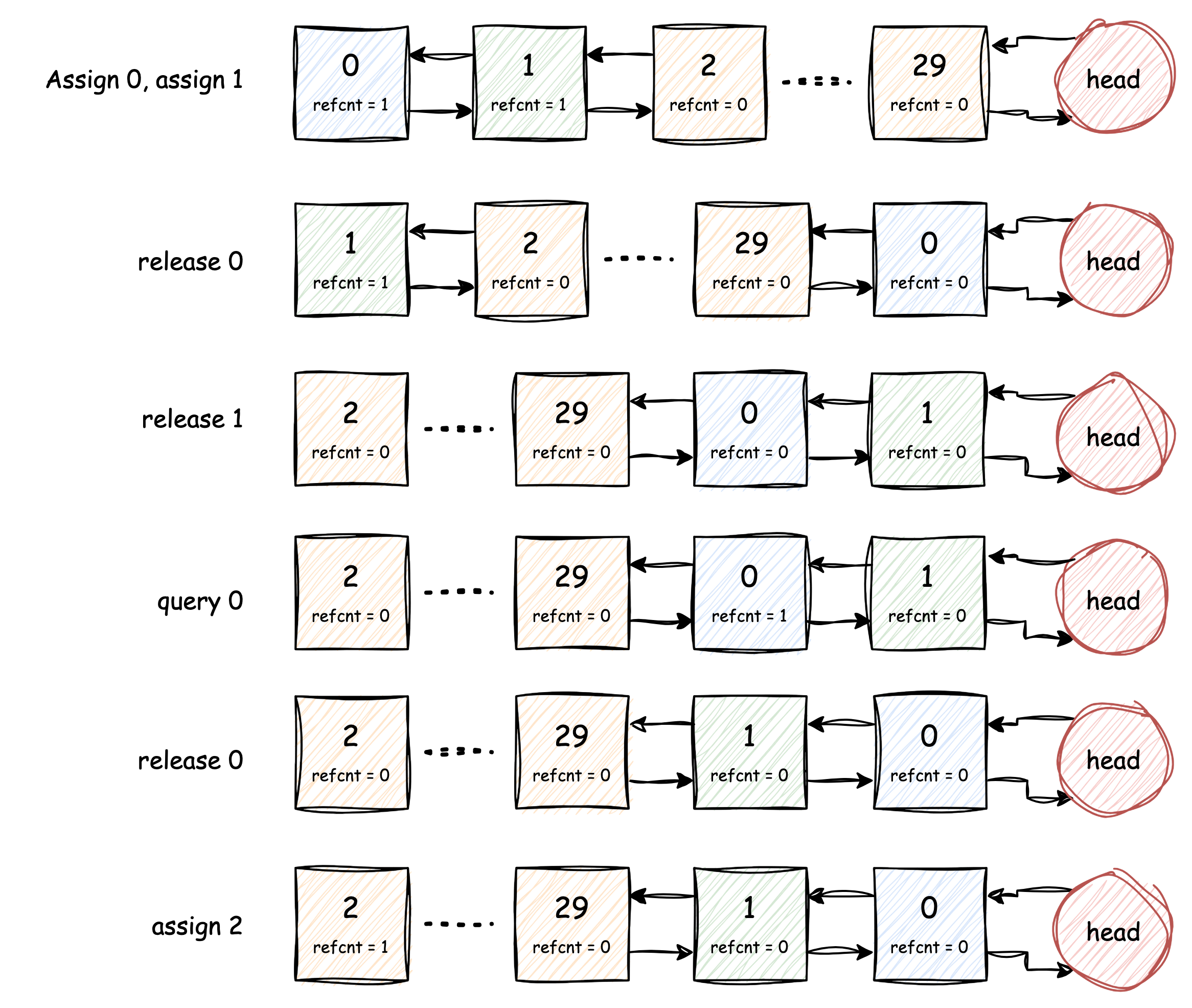

There are three main BCache

operations: "query", "assign" and "recycle", let's look at the "assign"

first, because the cache should be completely empty at the beginning, so

that nothing will be found through "query".

Assign an available block frame requires finding a frame that hasn't

been referred, which means refcnt == 0. The finding process

will start from head.prev, which is the

buf[29]. Since there is no block frame is referred when

system is just started, the first block frame will be the

buf[29], and if there is another disk request that needs

another block to be loaded into memory, the buf[28] would

be assigned, and so on.

Based on the principle of locality, LRU assumes the data that is most recently used would have high possibility to be used again. On the contrary, the "Least Recently Used" block, would have less possibility to be used again.

But how is a block frame considered as "used"? So once a block frame

is used by some syscall, the Buf.refcnt will never be zero,

a non-zero refcnt indicates the Buf

is "being" used. Only if there is no syscall accessing the Buf,

the state of this very block frame could be considered as "used".

Hence, we can check the "recycle" logic in the brelse(),

if b.refcnt == 0, the block frame will be moved to the head

of the linked list, because this Buf

is most recently used. Now we can understand why the "query" code

traverses the cache from the head.next, because from this

direction, the most recently used block will be queried first, that's

the most efficient way.

As time goes by, the least recently used block frame will sink to the

tail, when a new empty block frame is needed, the "assign" logic

traverses the list from the tail, which is also the

head.prev.

The following diagram depict such kind of process:

Assume buf[0] and buf[1] are assigned and

being used. Firstly buf[0] is released and is put to the

head, then buf[1] is released, and is also put to the head,

at the time, buf[1] is closer to the head than

buf[0].

But next, the buf[0] is queried, and released again,

that makes it returned to the head position, because the most recently

used block is buf[1].

Finally, buf[2] is assigned since it's never used

before, we can also imagine once buf[2] is released, it

will be put to the head as well.

4. VirtIO Device

With many different layers above, now we arrive at the bottom layer: disk layer. At this layer, the data will be read from or written to a "real disk".

The phrase real disk was quoted by quotation marks, because we have known in the first chapter that our OS is running on the qemu virtual machine, and according to the runner command, we can see the disk is actually an image file placed in the host machine:

1 | runner = "qemu-system-riscv64 -S -s -machine virt -bios none -m 128M -smp 3 -nographic -global virtio-mmio.force-legacy=false -drive file=../mkfs/fs.img,if=none,format=raw,id=x0 -device virtio-blk-device,drive=x0,bus=virtio-mmio-bus.0 -kernel " |

In a virtual machine, the IO devices are usually virtual devices. For example, a virtual disk often has two parts, the first part acts as a disk device connected to the virtual machine, and can only be seen in the guest machine; while the second part is a program that is located in the host machine, responsible for data transformation.

Looking at the "runner" command, the "-drive" argument set the file "fs.img" as the disk image, and the "-device virtio-blk-device ..." uses the "virtio-blk-device" to emulate block device. The "virtio-blk-device" adds a virtio block device in the guest machine that mount on the "virtio-mmio-bus.0", and sets the image file as real data store in the host machine. So that with the above configuration, we should see the virtio device in the guest machine:

1 | qemu-system-riscv64 ... -monitor stdio |

The info qtree command in qemu monitor prints the device

tree of the guest machine, we can see the device "virtio-blk-device" is

mounted on the bus: virtio-mmio-bus.0, its address starts

from 0x0000000010001000, and it has the size range of

0x0000000000000200, which is 512 bytes.

So far we have encountered some concepts that we are not familiar with, such as "virtio-blk-device" and "virtio-mmio-bus". So what exactly is “virtio”?

Basically, virtio is a type of standard that aims to provide a general abstraction of devices.

With the virtio standard, common hardware can be virtualized in guest machine, as virtual devices. Virtio standard defines many types of devices, such as block device, net device, console, scsi and gpu.

We have slightly mentioned before, about the two parts consist of virtual disk device. In the same way, virtio actually works based on a frontend and a backend, and they exchange data through shared memory and a kind of ring queue called "virtqueue".

According to the virtio specification:

In virtio standard, each virtqueue can consist of up to 3 parts:

Descriptor Area - used for describing buffers

Driver Area - extra data supplied by driver to the device

Device Area - extra data supplied by device to driver

In the previous version of virtio, the above parts were called "Descriptor", "Available" and "Used", which are also adopted in the xv6 code. Essentially, the data change between frontend and backend is achieved by those buffers, we'll see how they work together to do so afterward.

Besides, virtio also provides several ways to communicate between the frontend and the backend, such as virtio-mmio, which maps its address into memory space, so that the virtio backend can be accessed by ordinary memory operation; and virtio-pci, which takes pci bus to communicate with virtio backend. For more details, please also refer to the latest virtio specification.

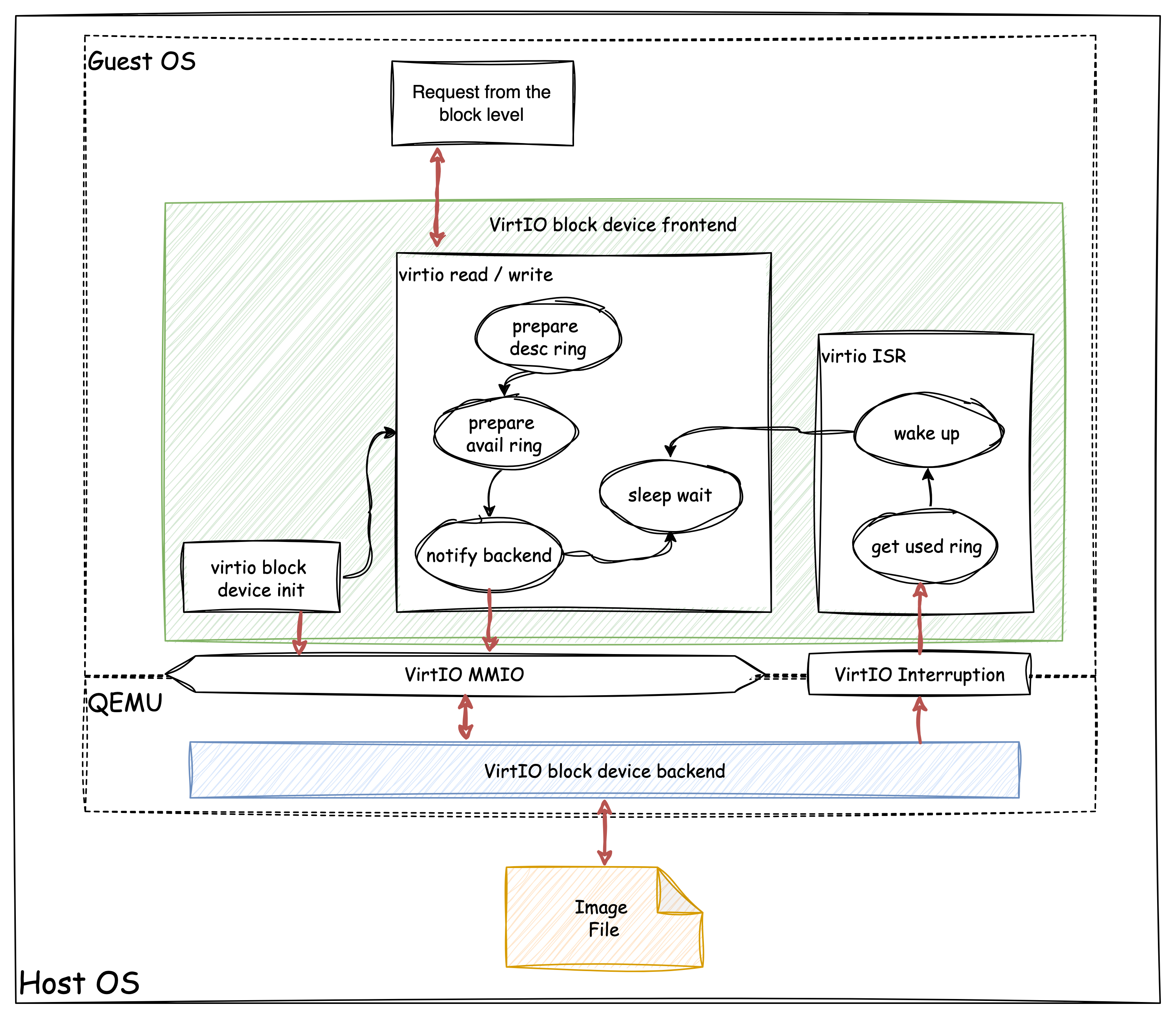

The following diagram shows how xv6 interact with qemu by virtio:

It clearly illustrates the frontend, backend and transport bus. When QEMU setup virtio block device for the guest OS (xv6), it implements the backend program as a virtual device, and maps the device control registers into address space of guest OS, this way is called virtio over MMIO. Besides, an external interrupt source specific for this virtio device is also connected.

The program(virtio_disk.rs)

within the xv6, act as the frontend to operate virtio, can also be

called as virtio driver. The driver initialize virtio device at the boot

stage, then once a block operation wants to read data from or write data

to the disk, the function virtio_disk_rw()

will be called. This function prepares the two parts of virtqueue:

descriptor and available, to build a virtio request that contains fields

such as request id, read/write flag, address of Buf

. After the request is prepared, it would notify the device that data is

ready. Since IO operation is relatively slow, there is no need to hold

the CPU waiting for response, at this time, the function will start

sleeping to wait.

Once receive the notification, the virtio device starts to read or

write data in to the image file, after operation is complete, the device

will trigger an interrupt so that an interrupt service routine located

in the guest OS could handle that interrupt. The operation response will

be fetched from the third part of virtqueue: used, then the virtio_disk_rw()

will be waken up too, so that it can finally return to the upper level

block operation.

Because the real code seems straightforward, I'll leave them for the readers to discover. FYI, xv6 chose split virtqueues format for device operation, see chapter 2.7 Split Virtqueues to get to know the definition of virtqueue structures. And for the specification of MMIO control registers, please check the chapter 4.2 Virtio Over MMIO.