/Xv6 Rust 0x06/ - User Space

Based on disk and file management, now we are able to store the user space program on the disk, and let them run after kernel started. But before that, there is still a topic we haven't covered: how does xv6 jump from kernel space to user space?

After all, the content we talked about in previous chapters is only limited in the supervisor level, even machine level, where the code has full control of hardware. However, the user space program cannot be granted such huge scope of control, then we should know how to jump from kernel space to user space, so that we could provide a safer environment for the user program.

In this chapter, we are going to find it out.

1. Jumping in the CPU Perspective

If you remember, there was a table in our second chapter that describes several CSRs that risc-v provides to user, some of them are responsible for mode switching.

Speaking of how to jump from supervisor mode to user mode, there would be the following questions that come up with in your mind:

- What kind of instruction is able to trigger the switching?

- After jumping to user mode, where exactly will the program go to?

- How to deal with the context and different memory space between two modes?

At first, let's recap the privilege mode switch that we've mentioned in the second chapter:

How does risc-v deal with the privileged mode switch?

.... RISC-V Privileged Specification Chapter 1.2 ...

A hart normally runs application code in U-mode until some trap (e.g., a supervisor call or a timer interrupt) forces a switch to a trap handler, which usually runs in a more privileged mode. The hart will then execute the trap handler, which will eventually resume execution at or after the original trapped instruction in U-mode. Traps that increase privilege level are termed vertical traps, while traps that remain at the same privilege level are termed horizontal traps. The RISC-V privileged architecture provides flexible routing of traps to different privilege layers.

.... RISC-V Privileged Specification Chapter 1.2 ...

Generally, when a trap happens, the address of where the cause the trap will be saved in

mepcorsepc, regarding the current privileged mode. After trap handled by specific handler, it should call eithermretorsretto return to the previous mode, which is stored in theMPPorSPPfiled of themstatus.

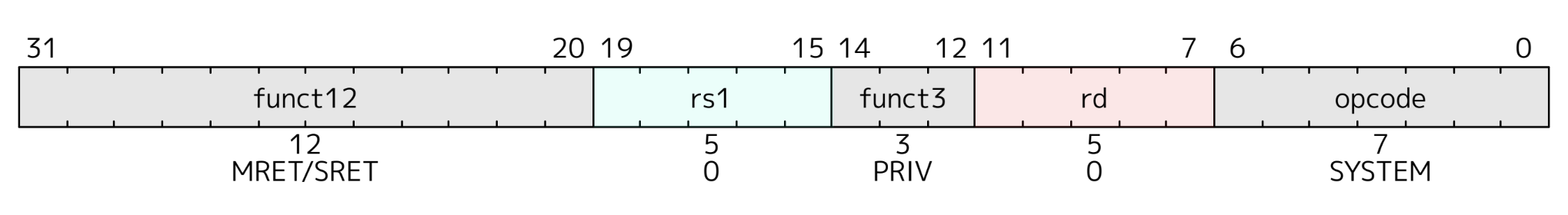

Let's take a close look at the sret instruction:

Apparently, SRET doesn't rely on any source or

destination register, so when using the SRET, we only need

to call the bare instruction.

According to the specification, xRET sets the

pc to the value stored in the xepc

register. Hence, before SRET is called, we could set

the address into the sepc, then once it is called, the

program will jump into the address.

So far, it looks SRET does a lot of things for us, so

that we'll no longer need to concern about the first two questions.

However, in risc-v architecture, no more support will be provided. Now,

for the question of context and memory space switch, we are on our

own.

Imagine the kernel is about to complete initialization, and program

is running on the supervisor mode. Now, the kernel should start creating

the very first process in the whole system, we call it

init. Assuming that a few milliseconds later, the process

structure has been created and all of the importance fields have been

set, next the kernel must think about runs the SRET

instruction, and hands the control of CPU to init.

But before calling the SRET, both the context and memory

space should be replaced as well, because:

- Context Switch: the context here means the general purpose registers, there are two main reasons that the context switch should be done; first, the value of registers in supervisor mode must not be leaked to user mode for safety; second, in other cases like syscall or interrupt handling, we need to make sure when go back to user mode, the user process can resume correctly with all registers still store the origin values, that requires properly context switch too.

- Memory Space Switch: we have known that there is a kernel page table dedicated for kernel code, if we don't set the user process page table after switch mode, then the user process is able to access kernel memory space, which is extremely dangerous; besides, kernel page table does not hold user code in the text section, makes the user process unable to get its code.

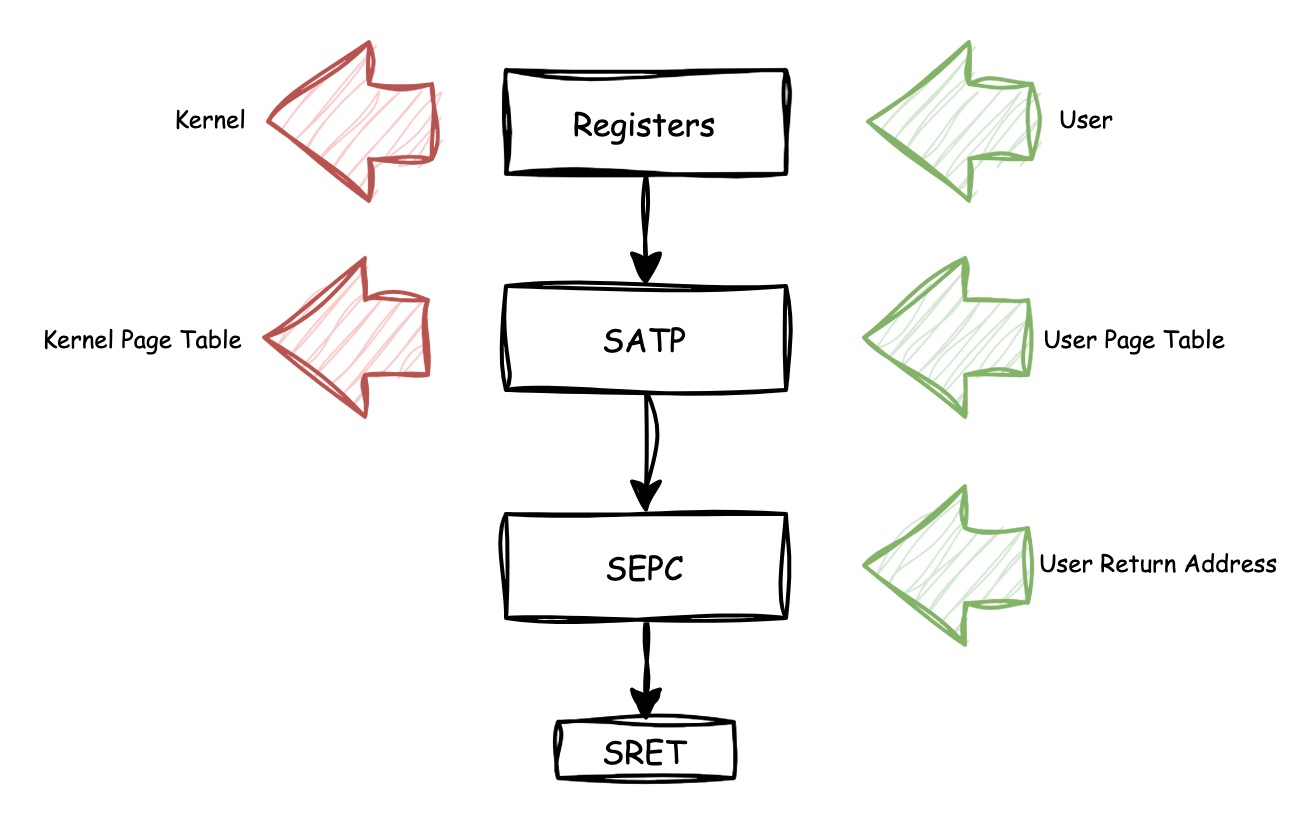

Therefore, it's essential for kernel to take care of the context and memory space switch. The following is a diagram that shows the process of switching from supervisor mode to user mode:

Firstly, there should be some memory spaces allocated to hold the

pre-stored registers, additionally, the page table is created along with

creating of Proc structure (see inner_alloc()).

Secondly, the address of user process page table should be set into

satp, and the value of general purpose registers should

also be restored.

Finally, put the user space address (virtual address) into the

sepc, and call SRET at the end of the program.

After that, everything is changed to user space!

2. Trap and Trampoline

As there is some extra work that needs to be done before switching into user space, where does that need to happen?

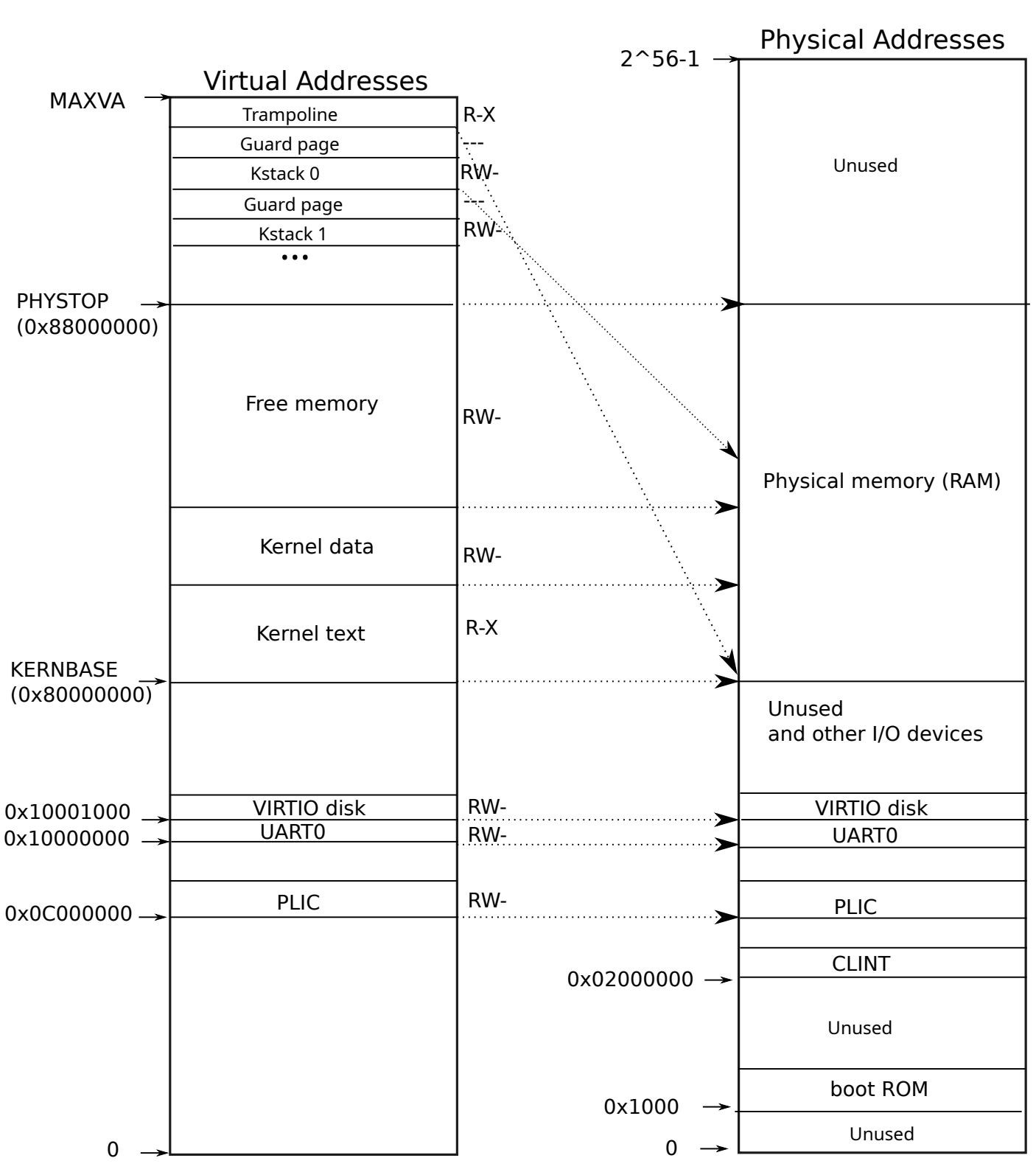

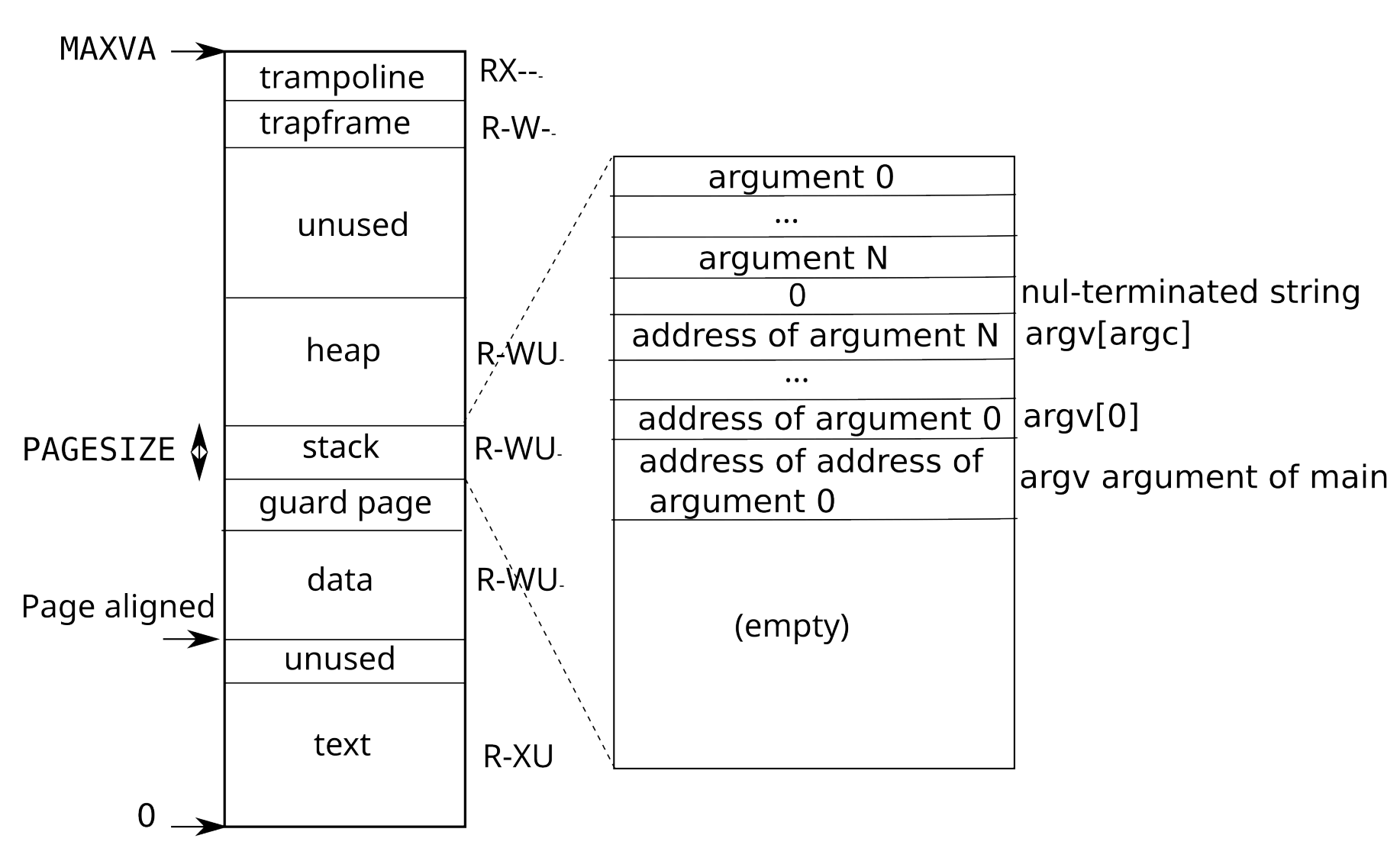

We haven't mentioned the full address layout of xv6 in previous chapters, now it's time to show both kernel address layout and process address layout, these are very helpful to understanding the concept of "trampoline". Let's have a look! (The following diagrams are taken from the xv6 book, figure 3.3 and figure 3.4)

Above is the kernel address layout that includes virtual address space on left and physical address space on right. Follow the sequence of low address to high address, which is also bottom to top, the kernel address space can be divided into several parts (please note that the mappings between virtual space and physical space in kernel is a little complicated, we'll introduce them together, hopefully, the what we have learnt in previous chapters can help us for better understanding):

- (Physical) boot ROM: qemu actually provide this

- (Physical) core local interrupter: it contains a timer

- (Physical + Virtual) PLIC, UART0, VIRTIO disk: we have talked about them before

- (Physical + Virtual) Kernel memory:

- Text section contains all kernel code

- Data section stores some constants and statics

- Free memory holds all other data, including kernel objects and

process data (refer to

kalloc)

- (Virtual) Process stacks: each process has it own stack, which is allocated here, actually they are allocated from the "Free memory" section

- (Virtual) Trampoline: interesting section, according to the above diagram, it maps to the address near the KERNBASE, which is also the same address as the text section. Is this a coincidence?

As the kernel vm init code shows:

1 | // vm.rs |

The value of virtual address Trampoline is

MAXVA - PGSIZE, which means the trampoline section is

located in the top address and takes one page of space. This is

consistent with the above diagram.

However, it maps to the physical address: trapoline_addr, which is actually a label "trampoline" that is defined in the trampoline.S:

1 | ### trampoline.S |

Now I suppose you already know why it maps to the read-only text

section, because the trampoline points to some code that

used to handle the trap and trap return.

The location of the trampoline is intentional. Let's see the process address layout:

I guess most of the sections in the above diagram are very familiar to you, because they are no difference from other modern operating systems, except for the trampoline.

The most obvious similarity is that the address of trampoline in

process address space is exactly the same as it in kernel address space.

Why? Because each time a trap happens in user mode, risc-v switching to

supervisor mode, and then redirect the program to uservec,

which is the trap handler address, we'll see the registration of the uservec

afterward.

First, let's take a close look at it:

1 | ### trampoline.S |

Apparently, once the program goes to it, the value of many registers

are saved into Trapframe,

which is allocated in the inner_alloc().

Basically this process is the context switching that we discussed

before. All user registers are saved.

But the most important line is csrw satp, t1, which

installs the kernel page table, you may ask a question at this stage:

does that mean, before this line, although the risc-v has been switched

to supervisor mode, the xv6 still running on user address space?

Exactly! That's the essential reason of trampoline section should

share the same address between the kernel space and user space.

Otherwise the uservec

cannot be correctly located if trap happens. Because there is no place

that allows page table switching before trap.

Additionally, after installing the kernel page table, what if an

external interrupt happens? At this moment, the trap vector is still set

to uservec,

if the kernel space and user space don't share the same trampoline

address, there would be some chance to jump into an undefined address

that is translated by kernel page table.

2.1 trap handler

After done the context and memory space switching, at the end of the

uservec,

it jumps to the real trap handler function, which is called usertrap():

1 | // trap.rs |

Basically, the usertrap()

handles interrupts, exceptions and syscalls. But before recognizing any

of them, it first set the stvec to the kernelvec

which is the trap handler specific for kernel space.

1 | ### kernelvec.S |

In the same way, there are also context save and restore in it, the only difference is the kernel has its own trap handler:

1 | // trap.rs |

Since there is no syscall in kernel space, the kernel trap handler only handles interrupts(external, software and timer) and exceptions, which makes it simpler than user trap handler.

Let's go back to the user trap handler, after all we just explained the first line of it.

After saving the user program counter into trap frame, in the next it

mainly deals with the three trap reasons: syscalls, interrupts and

exceptions. We'll cover these parts in the next section, now we are

going to the final call: usertrapret():

1 | // trap.rs |

In this function, the uservec

is set to the stvec, and here is the only place the user

trap vector is set. Next, saving the kernel space context to the trap

frame so that they can be resumed in the following trap. After that, set

some registers for preparation to make sure the user mode can be

correctly switched afterward. At last, the address of userret

is called along with the page table address, the userret

does the reverse operation compare to the uservec.

3. Syscalls, Interrupts and Exceptions

We have taken a glance at the trap handler previously, now we are going to look deeper into the handlers.

There are three types of trap, and will happen in the following circumstances respectively:

- Syscalls: they are the bridges between user program and kernel, since there are plenty of operations that a user program will be needed for implementing some logic, however the operating system cannot trust the user program to do so because those operations are dangerous running in user mode. So kernel provides an interface layer so that user program can just call it to get what it needs, and delegates the job to kernel.

- Interrupts: we have learnt that the effective interactive method between the peripherals and the OS is through the external interrupt, like UART and VIRTIO, and also a hardware timer we haven't talked about. The CPU needs to handle these interrupts immediately because interrupts usually don't wait in a line, that requires a trap to suspend whatever is running currently, and turn to handle the interrupt.

- Exceptions: please imagine if a user program accesses an address that is out of the range that allows it to access? No matter accidentally or maliciously, this action needs to be stopped. Therefore, if a program (both kernel code and user code) does some disallowed operation, the CPU trapped, and let the trap handler to deal with what to do next.

3.1 Syscalls

According to previous code in the usertrap():

1 | //trap.rs |

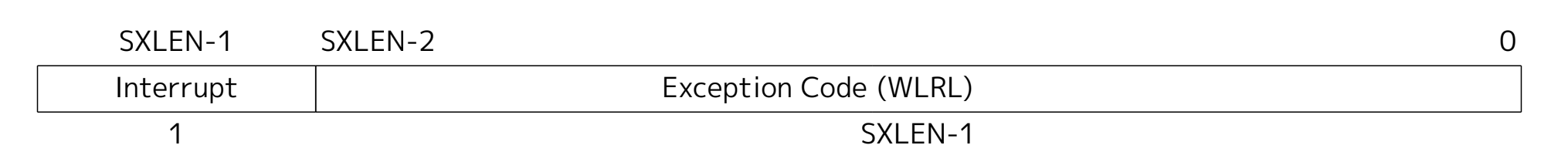

When the value of scause is 8, indicates a syscall

happened.

As we can see, the scause has two parts, interrupt and

exception code. Since there is only 1 highest bit to indicate the

interrupt status, as long as the bit equals 1, an interrupt

happened.

Look into the syscall(),

we will find how xv6 handles syscalls:

1 | // syscall.rs |

Basically, it retrieves the syscall number from trap frame, and then

using the number maps the real syscall function from a constant array.

And look at the array you may find many familiar functions such as

sys_open, sys_fork and

sys_read.

The above is how kernel handles syscalls. But you may curious how the user code triggers the syscall in user space? Let's move on to user code:

1 | // user/src/ulib/stubs.rs |

1 | // user/src/ulib/usys.S |

Actually, there are several stub functions located in user code, and

each stub relates to a few lines of assembly code, which do only one

thing: call ECALL by syscall number as a parameter.

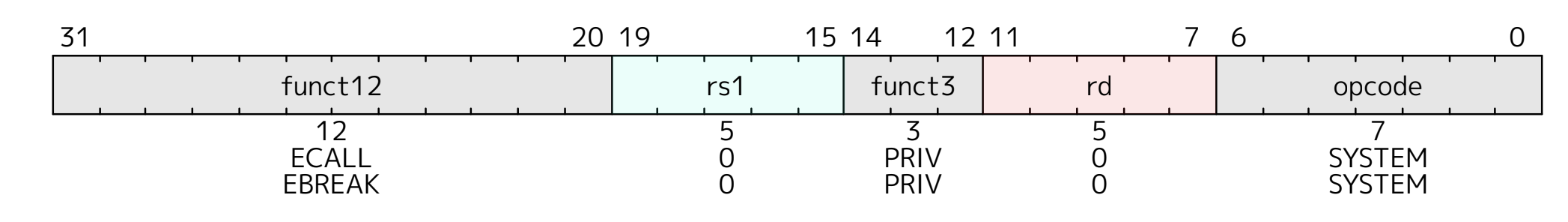

In the above diagram, the instruction ECALL and

EBREAK share the same structure. And they behave similarly

as well. Beneath the ECALL, it actually generates an

"environment-call-from-U-mode" exception if it is called in user mode

and performs no other operation. So we can regard the ECALL

as a special exception. Similarly, EBREAK generates a

breakpoint exception and performs no other operation. It's usually used

by a debugger.

Essentially these two instructions only switch user mode to supervisor mode then do nothing further, this simple behavior leaves the operating system enough space to do whatever it wants, such as syscall or debug.

ECALL and EBREAK cause the receiving privilege mode’s

epcregister to be set to the address of the ECALL or EBREAK instruction itself, not the address of the following instruction.

Refer to the above quote, the epc will be set to the

address of ECALL itself, that's why in the usertrap(),

it runs tf.epc += 4;

before calling the syscall().

3.2 Interrupts

To handle interrupt, the devintr

needs to be called:

1 | // trap.rs |

Inside the devintr,

there are still a few branches to differentiate more cases:

1 | // trap.rs |

To understand the branches, we may need to investigate how many

reasons the scause stands for:

| Interrupt | Exception Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | Reserved |

| 1 | 1 | Supervisor software interrupt |

| 1 | 2-4 | Reserved |

| 1 | 5 | Supervisor timer interrupt |

| 1 | 6-8 | Reserved |

| 1 | 9 | Supervisor external interrupt |

| 1 | 10-12 | Reserved |

| 1 | 13 | Counter-overflow interrupt |

| 1 | 14-15 | Reserved |

| 0 | >= 16 | Designated for platform use |

| 0 | 0 | Instruction address misaligned |

| 0 | 1 | Instruction access fault |

| 0 | 2 | Illegal instruction |

| 0 | 3 | Breakpoint |

| 0 | 4 | Load address misaligned |

| 0 | 5 | Load access fault |

| 0 | 6 | Store/AMO address misaligned |

| 0 | 7 | Store/AMO access fault |

| 0 | 8 | Environment call from U-mode |

| 0 | 9 | Environment call from S-mode |

| 0 | 10-11 | Reserved |

| 0 | 12 | Instruction page fault |

| 0 | 13 | Load page fault |

| 0 | 14 | Reserved |

| 0 | 15 | Store/AMO page fault |

| 0 | 16-17 | Reserved |

| 0 | 18 | Software check |

| 0 | 19 | Hardware error |

| 0 | 20-23 | Designated for custom use |

| 0 | 24-31 | Designated for custom use |

| 32-47 | Reserved | |

| 48-63 | Designated for custom use | |

| >= 64 | Reserved |

It looks quite complicated, but in this stage we only need to care about two scenarios:

(scause & 0x8000000000000000) != 0 && (scause & 0xff) == 9Above condition filters out the external interrupt so that once the program goes into this branch, it means there was an external interrupt triggered by some device.

In current xv6 source code there are only UART and VIRTIO supported, but it won't be too hard to add other devices to the system. In real operating system the interrupt handlers for specific devices are often put in some software package called driver.

After handles the external interrupt,

plic_complete(irq)should be called to reset the PLIC so that new interrupts can be triggered again, otherwise the PLIC will keep waiting for handler to do its work.scause == 0x8000000000000001This condition only filters software interrupt. But why does it handle the timer interrupt?

In the

timerinit(), the timer interrupt handler is set totimervec, hence, once timer ticked, onlytimerveccan handle the interrupt. And if you see it closely, thetimervectriggers a software interrupt in the end. The user trap handler wouldn't handle the timer interrupt until now.Why bother with all this? Because in previous versions of risc-v, the time compare registers can only be accessed in machine mode, so that there's no way for kernel to reset the timer registers in supervisor mode.

Refer to the xv6 book version 3 (page 56):

A timer interrupt can occur at any point when user or kernel code is executing; there’s no way for the kernel to disable timer interrupts during critical operations. Thus the timer interrupt handler must do its job in a way guaranteed not to disturb interrupted kernel code. The basic strategy is for the handler to ask the RISC-V to raise a “software interrupt” and immediately return. The RISC-V delivers software interrupts to the kernel with the ordinary trap mechanism, and allows the kernel to disable them.

Fortunately, risc-v now supports the "SSTC" extension. Here is the documentation about the "SSTC", which was ratified in 2021. The SSTC extension "provides supervisor mode with its own CSR-based timer interrupt facility that it can directly manage to provide its own timer service."

QEMU has supported this extension back to 2022. And the newer version of xv6 has changed to SSTC, see here.

3.3 Exceptions

The exceptions are mainly related to the scause. And as

long as the returns 0, means an exception happened:

1 | // trap.rs |

The handling of exceptions is quite simple and straightforward: it

panics. The value of scause, sepc and

stval will be printed along with panic. Those values are

really useful to help investigate the root cause of exceptions. The

scause records the exception reason, the sepc

holds the virtual address of instruction that causes trap, while the

stval is written to different useful information based on

different value of scause.

We have reviewed the details of exception types before, and the

following are what kinds of value will be written into the

stval:

| Exceptions | Value of stval |

|---|---|

| Breakpoint, address-misaligned, access-fault, page-fault | Faulting virtual address |

| Access-fault or page-fault caused by misaligned load or store | The virtual address of the portion of the access that caused the fault. |

| Instruction access-fault or page-fault | The virtual address of the portion of the instruction that caused the fault |

| Illegal instruction exception | Faulting instruction bits |

| Other traps | Zero |

These three registers are very helpful when kernel crashes.

Especially in the debugging process of xv6, it would be common to

encounter the stack overflow problem, since there is always a "guard"

area between two stacks, as long as stack overflows, there would be an

access fault exception thrown, in this moment, checking the value of

sepc and stval will help to find the code

position.

4. Init Process

With all previous content as the foundation, now we can finally discover how the xv6 starts its first process: init process.

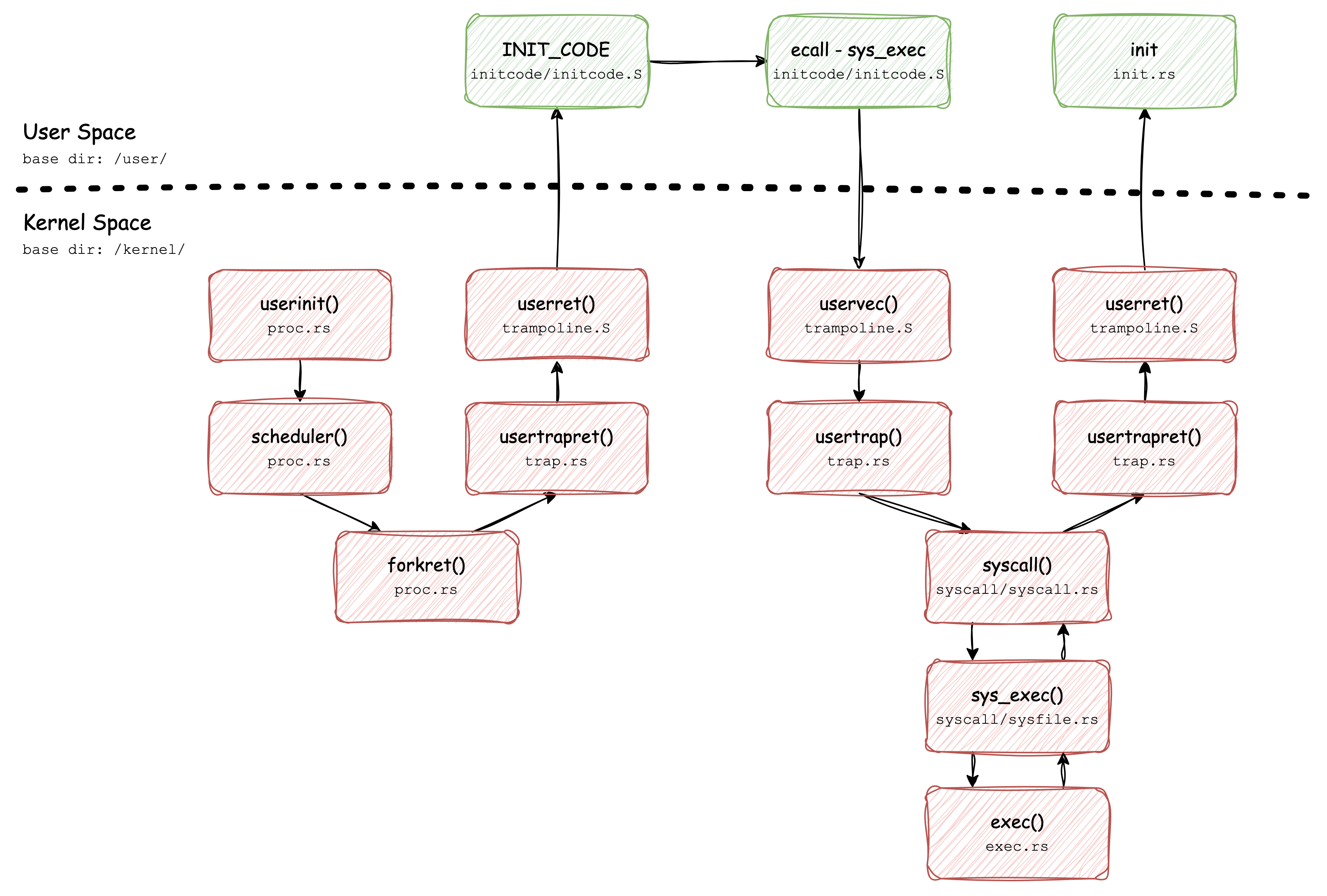

The following diagram shows the main sequence of kernel builds up init process and then executes it as the first user process:

Some parts like switching between user mode and supervisor mode have been covered before, next we are going to focus on the other parts.

4.1 User Init

First, let's see how the init process is created:

1 | // proc.rs |

The userinit()

function does three important things:

- Allocate a process structure that holds stack, page table and trap

frame. The allocation mainly covered by the

allocproc(), which picks an unusedProcstructure to hold init. - Load code into memory at user space, which is performed by the

uvmfirst()that maps theINIT_CODEinto page table as the text section. - Set entry point as 0 in virtual address, and then set status to

RUNNABLE.

Looking at the INIT_CODE

you'll find there are only binaries. In fact, these binaries come from

the compile result of initcode.S:

1 | ### user/initcode/initcode.S |

The above code is quite simple, it only calls SYS_exec

syscall with /init\0 string as the argument. Since the

compiled binaries are very simple the xv6 can even hardcoded it as a

constant, this will omit the step to load it from file system.

Apparently, the INIT_CODE

is like a step-stone for initialization, the only thing it performs is

to call SYS_exec syscall to replace its code text as the

program /init. I'm sure you already knew the responsibility

of the exec syscall in POSIX, the SYS_exec is

just like that. We'll talk the /init soon later.

Besides, if you look into the implementation of the uvmfirst(),

it loads the INIT_CODE

at virtual address 0x0, and since the trapframe.epc is also

set to 0, once the init process is put on cpu, the first line of code it

would run is start in the INIT_CODE.

4.2 Running On CPU

Once the init process is well prepared, then the kernel continues its

init procedure, and runs the last step: scheduler().

We have learnt in the fourth chapter what the scheduler will do:

traverse the proc list to find if there is any process is on

RUNNABLE state. Here we only have one process that is

runnable: init process. So the scheduler will call swtch

to switch the context and return. But where will it be returned?

If you remember, we have mentioned this back in chapter-4, the return

address is set in the inner_alloc():

1 | //proc.rs |

Since the scheduler()

is running on kernel space, we can't return to user space directly after

switch, that what the forkret

is responsible:

1 | const FIRST: AtomicBool = AtomicBool::new(true); |

It's simple and clear, at the first time the forkret

is called, the file system needs to be initialized, this step mainly

reads the SuperBlock from disk, please refer to chapter-5

for more details.

After that, usertrapret()

will be called, we have seen that in previous sections, at this very

step, the epc will be set to trapframe.epc,

which is 0, and once SRET is called, the init process will

finally start to run.

4.3 Syscall Exec

Following the previous sequence diagram, the INIT_CODE

only execute ecall to get in trap again, and trigger the

SYS_exec.

As we already knew how syscall is handled, let's go check the

implementation of sys_exec():

1 | pub(crate) fn sys_exec() -> u64 { |

Most of its jobs fetch the argument along with ecall, it

will need some effort to do so because the argument is at user space and

needs to be copied into kernel space. But these parts are not very

important, now we deep dive into the exec():

1 | pub fn exec(path: [u8; MAXPATH], argv: &[Option<*mut u8>; MAXARG]) -> i32 { |

Since this function is very long, the code pieces only contain a few main steps. For more information please directly see the raw code.

In short, the final target of the exec()

is replacing the current process into a new one, but keeps the current

process structure and pid. Through this procedure, many things will get

replaced, such as program code, constants, variables.

In order to achieve that, first we need to load the

/init into the memory, that's what the

namei(&path) does. Once we have the inode points to

/init in our hand, we can read the content of

/init.

In the above code, it first reads the ELF header as the xv6 file follows the ELF format. The ELF header records the section information, including program segments that are described in the program header. These segments are text, data and others, which are necessary for the program to be executed.

Through the loadseg() function, all program segments are

loaded into memory and mapped into a newly created page table, this page

table will be the new page table that replaces the old one. Expect for

the program segment loading, the arguments passed along with the

SYS_exec are also copied into stack.

At last, the page table is replaced, and the old one is released, the

epc is set to elf.entry which points to the

first line of code of /init. At this moment, a new process

is finally born.

4.4 Init

We haven't seen what the init looks like, at the end of this article, let's have a look:

1 |

|

There isn't too much code in it, the whole logic can be split into two simple parts:

- Open Console as stdin, stdout and stderr

- Fork itself

- For the child process, call

SYS_execagain to replace itself as the shell program - For the parent process, which is also the init process itself, wait

for it child to be exited, and if it happens that the child process also

has its children, then the grandchildren processes will be regarded as

orphans. Therefore, along with the exit of the child process, all orphan

processes will be reparented to init. (See

exit()for details)

- For the child process, call